Orfèvrerie Ercuis

Tradition and craftsmanship since 1867

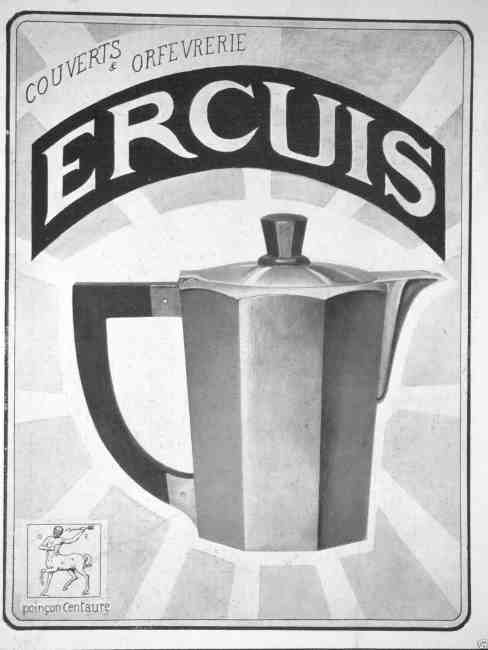

Ercuis advertisement, 1929

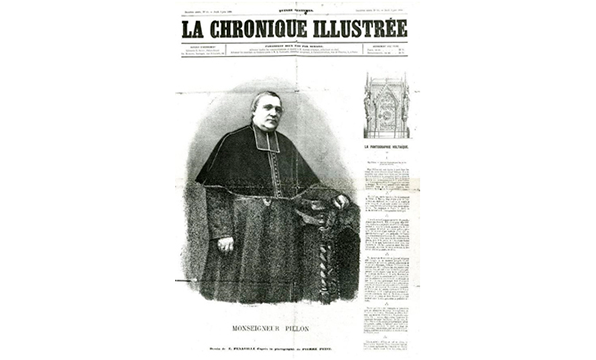

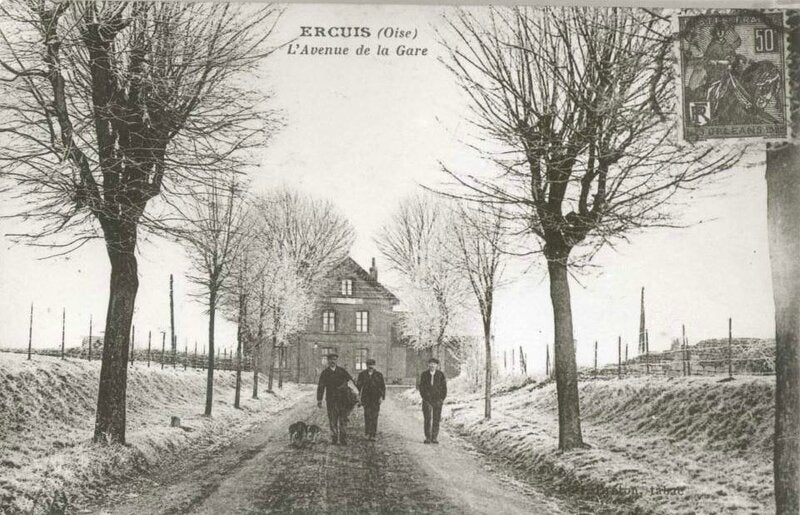

The origins of Ercuis goldsmith's house date back to 1867, when Father Adrien Céleste Pillon, a parish priest in the village of Ercuis, 50km from Paris, founded a religious goldsmith business to make silver- and gold-plated pieces.

To finance the business, Pillon set up a local newspaper, which he also used as a means of advertising his creations. However, the business was soon taken over by Léon Durand, the former production manager of the Clichy glassworks, who redirected it towards the art of the table. In 1880, they opened their first shop in Paris.

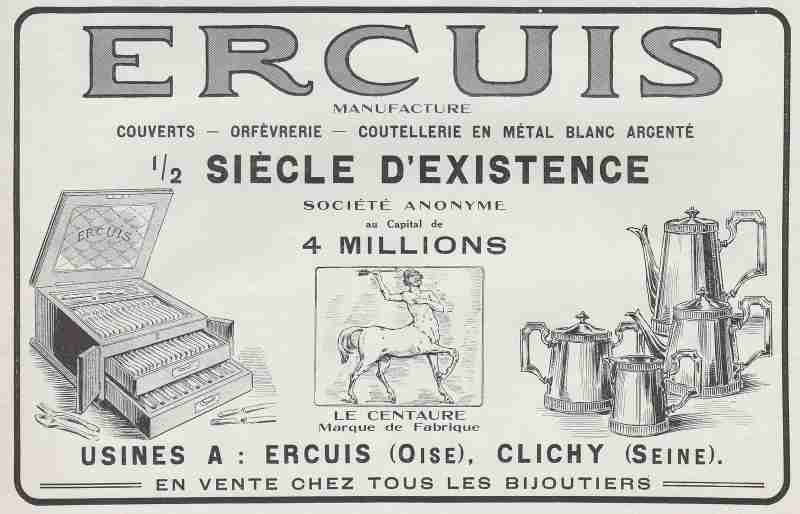

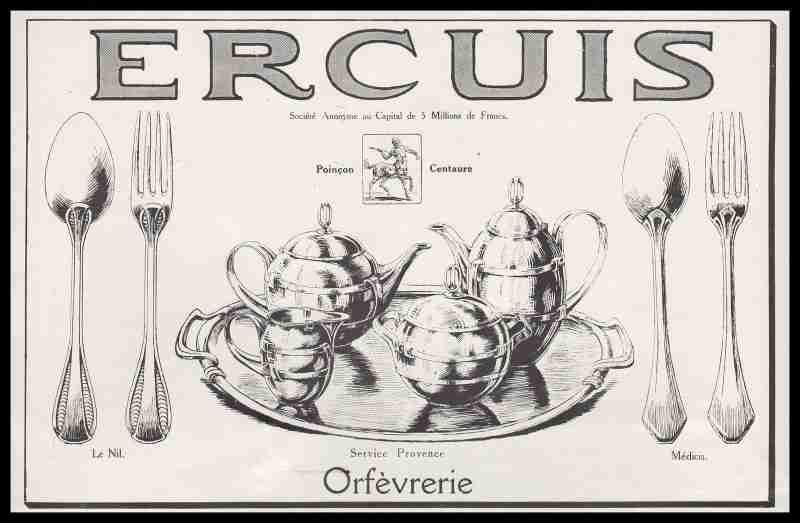

In 1886, Ercuis goldsmiths signed an agreement with the producer George Maës, adopting his ‘poinçon carré’, the official contrast in France for silver-plated metal, represented by a centaur, which has become the symbol of the firm to this day. The Maës family spearheaded the growth and expansion of the house for three generations.

Throughout the 20th century, the house gained prestige and recognition, participating in various Universal Exhibitions, equipping the great hotels of the Côte d'Azur, the Côte Basque and Paris such as the Pavillon Henri IV, and receiving important commissions such as the silver-plated pieces for the ocean liner ‘Le France’ or for the Orient Express.

From 1980s onwards, the company became a public limited company and changed hands several times. Today, the brand is owned by the Italian group Sambonet.

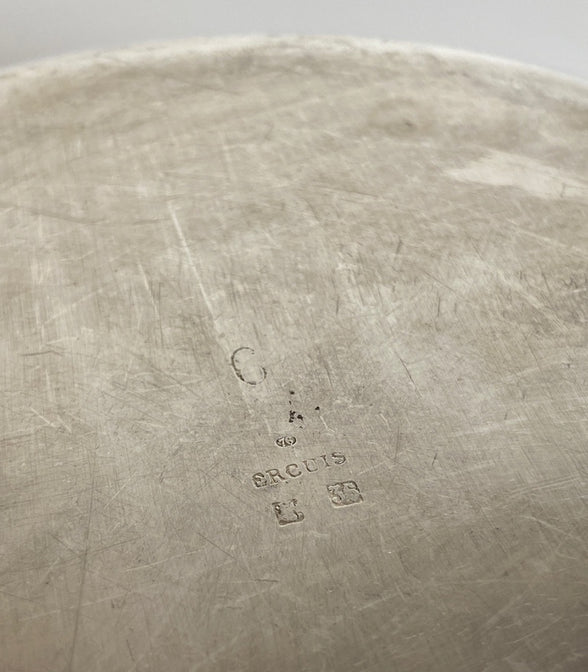

Ercuis hallmarks

The Ercuis pieces bear at least two hallmarks: the goldsmith's mark and the quality hallmark.

- The goldsmith's mark is represented by the inscription ‘ERCUIS’.

- The hallmark may be represented by the ‘poinçon carré’, the official French contrast for ‘metal argenté’, or by indicating the percentage of silver with each number in a square. The Ercuis ‘poinçon carré’ includes a centaur with the initials ‘OE’ identifying the house, and the indication of quality in Roman numerals: I or II, depending on the microns of silver in the piece.

The high quality of the silver plating applied to their pieces makes them of superior value on the antique market.

Boutique Ercuis at number 64 of Rue de Bondy, Paris

Boutique Ercuis at number 64 of Rue de Bondy, Paris

Portrait of Orfèvrerie Ercuis founder, Adrien Céleste Pillon

Ercuis hallmarks: the rhombus is used for silver pieces, and the square is the ‘poinçon carré’ for silver metal pieces.

Ercuis advertisement, 1922

Ercuis advertisement, 1926

Ercuis advertisement

Street of the station in the village of Ercuis, in the Oise region