The ‘bollo Suizo’

A lifelong sweet from Madrid

The ‘bollo Suizo’ is a classic pastry from Madrid that dates back to the 19th century. Despite its name, it is not of Swiss origin, but is a Spanish creation, specifically from Madrid.

It owes its name to the Confitería Suiza, a very popular establishment in the Spanish capital at the time. Opened in 1845, this confectionery was located at number 6 Puerta del Sol and became famous for the production of this pastry.

Over time, the Suizo became one of the most popular products in Madrid's pastry shops, becoming part of the traditional breakfast or afternoon snack of many families.

Behind the Confitería Suiza was a family of Swiss origin, the Fundérichs, who decided to settle in Madrid and open their own confectionery business. The surname Fundérich has remained associated with the prestige of the establishment, which not only offered confectionery, but also chocolates and sweets with European influences, something that was highly appreciated by Madrid's high society at the time.

The confectionery was an important social meeting point in Madrid. During the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, it was frequented by intellectuals, politicians and people from high society who went there not only to enjoy its sweets, but also to participate in gatherings and conversations in an elegant atmosphere. Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, who attended this café until the end of his life, used to sit at one of the tables next to the doors of the confectionery. The legacy of the Confitería Suiza lasted for decades, and although the original establishment closed its doors in the mid-20th century, it left an indelible mark on Madrid's confectionery tradition.

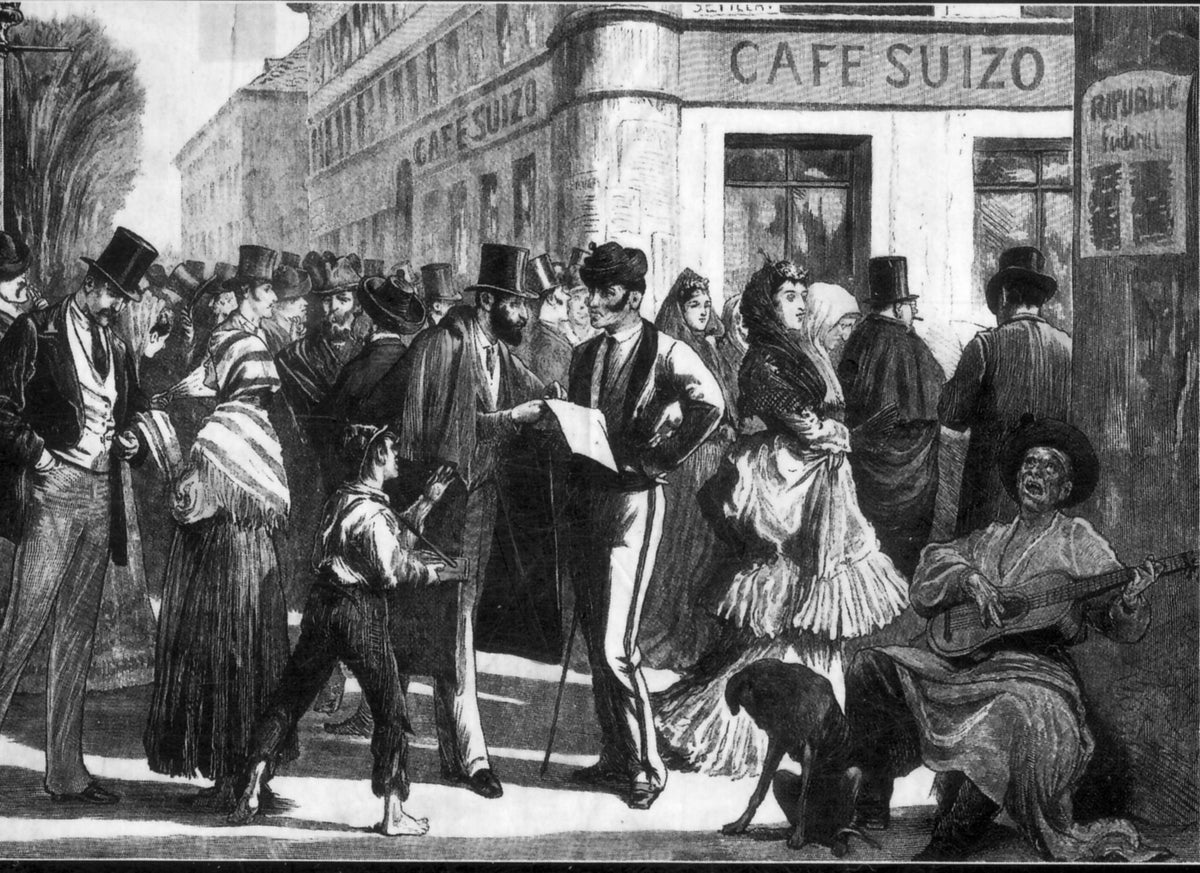

Drawing with several Castilian men in front of the Cafe Suizo in Madrid, 1873

Café Suizo, 1871

Gathering at the Café Suizo

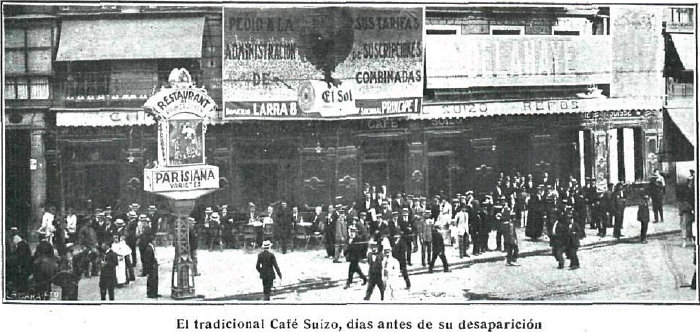

Façade of the Café Suizo located on the corner of Calle de Alcalá and Calle de Sevilla, Madrid, 1919. Source: Library of the Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza

Café Suizo days before its disappearance